Coming this fall:

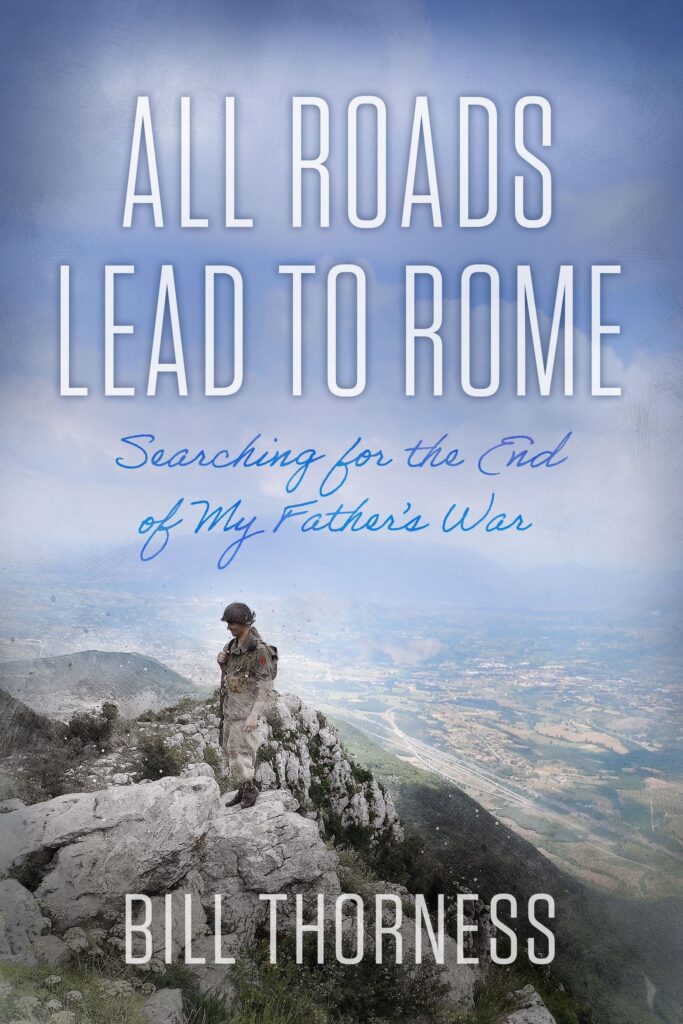

All Roads Lead to Rome: Searching for the End of My Father’s War

An exploration of family, history, memory and the ravages of war. To be available December 1 from Potomac Books, University of Nebraska Press

Preorder through Bookshop.org — support indie bookstores.

Related Links:

“We Have Always Owed Our Soldiers More,” Op-ed, May 26, 2024, St. Paul Pioneer-Press

My Substack column: billthorness.substack.com